Books

Yellow Robe, Red Flag A short biography of Rahul Sankrityayan

Most of this short book was written between 1990 and 1991 with the intention of publishing it for Rahul Sankrityayan’s birth centenary in 1993. However, I misplaced the manuscript and only rediscovered it amongst my late mother’s papers in April of this year, 2021. I had sent a copy to her but completely forgot having done so. At the time of writing the book, the only material in English I had at my disposal was Prabhakar Machwe’s Makers of Indian Literature; Rahul Sanskrityayan, Rahul’s Selected Essays, and the series of articles he wrote about his discoveries in Tibet for the Journal of the Bihar and Orissa Research Society. My other sources were Rahul’s friends and colleagues, including Bhadanta Ananda Kausalyayan, all of whom I had gone to India twice specifically to meet. I had also arranged to interview his wife Kamala but to my lasting regret the meeting had to be cancelled at the last moment. As soon as I rediscovered my manuscript, I obtained Alaka Atreya Chudal’s 2016 comprehensive biography of Rahul and have used it to correct some dates and the sequence of some events, and have also included a few episodes in Rahul’s life that I was previously unaware of

To eat or Not Eat Meat, A Buddhist Reflection

An issue that has long divided Buddhists is whether or not meat-eating is consistent with the Dhamma, the teachings of the Buddha. Both ancient and modern scholars have debated the matter, sometimes with considerable rancour. In this book a well-known Buddhist monk revisits the various arguments for and against meat-eating and examines them from a very different perspective. In doing so he also dispels several common misconceptions about Buddhism, highlights some rarely discussed problems associated with being vegetarian, and details some of the good reasons for becoming one. This book will make you look at Buddhism very differently. It might make you look at your next meal very differently too.

The Navel of the Earth

The Edicts of King Asoka

This rendering of King Asoka’s Edicts is based heavily on Amulyachandra Sen’s English translation, which includes the original Magadhi and a Sanskrit and English translation of the text. However, many parts of the edicts are far from clear in meaning and the numerous translations of them differ widely. Therefore, I have also consulted the translations of C. D. Sircar and D. R. Bhandarkar and in parts favored their interpretations. Any credit this small book deserves is due entirely to the labors and learning of these scholars.

The Broken Buddha Twenty Years On: Reviews, Personal Communications and Blog Comments.

When I published my book The Broken Buddha in 1990, I hoped it would stimulate debate and discussion amongst Western Buddhists about the course Western Buddhism should take, or not take. I received a few emails and letters about it but no more than a dozen, and somewhat disappointed, I left it at that and got on with my writing. Then in 2017, someone previously unknown to me, contact me and after saying how much he appreciated the book, told me that he had culled over a hundred assessments of and comments about the book from the internet, magazines, Buddhist newsletters and journals, and asked me if I would like to see them. I said I would and was quite surprised that the book had indeed triggered a great deal of debate, albeit quite unknown to me. Recently I thought it might be worthwhile to publish this material, so I have I added a few extracts from personal correspondence and the whole can be read below. Sometime in the future I will write a reply to my critics.

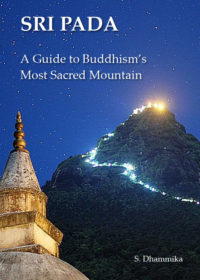

Sri Pada

Mount Sinai was considered sacred at a much earlier date, Mt. Fuji surpasses it in beauty and height, and Mt. Kilash evokes a far greater sense of mystery. Nevertheless, no other mountain has been revered by so many people, from such a variety of religions, for so many centuries as Sri Pada has. In Sanskrit literature Sri Pada is called variously Mount Lanka, Ratnagiri (Mountain of Gems), Malayagiri or Mount Rohana. This last name, like its Arab and Persian equivalent, Al Rohoun, is derived from the name of the south western district of Sri Lanka where Sri Pada is situated. In several Tamil works it is known as Svargarohanam (The Ascent to Heaven) while the Portuguese called it Pico de Adam and the English Adam’s Peak. In the Mahavamsa, the great chronicle of Sri Lanka written in the 5th century CE, it is called Samantakuta (Samanta’s Abode) while in modern Sinhalese it is often called Samanelakhanda (Saman’s Mountain).

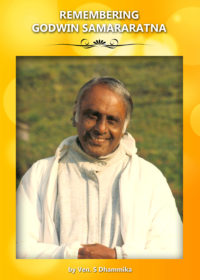

Remembering Godwin Samararatna

Excerpt of the book:

Based on a talk given at the

Nilambe Meditation Center on the 4th anniversary of his passing away

Godwin Samararatna was born on the 6th of September 1932 in Kandy, Sri Lanka. His father was the chief clerk of a tea estate at Hantane in the hills above Kandy and his mother was a simple up-country housewife. A younger sister died prematurely and an older brother died in a car accident on the day of his wedding. Godwin was the youngest of the two surviving brothers, Felix and Hector and his sisters were Dorothy, Matilda and Lakshmi. The family lived in a modest house at 145 Peradeniya Road just a short walk from the heart of Kandy. Everyone agrees that Godwin showed an interest in Buddhism from his earliest time, due mainly to the piety of his mother. When she went to the local temple of Poya days he always accompanied her and would sit listening to the sermons rather than play games as the other children did. Once he turned up at home with two which he had surreptitiously picked from someone’s garden. His mother asked where he had got them from and when he told her she went with him back to the house and made him return the vegetables.

Nature and the Environment in Early Buddhism

The first attempt to identify the plants in the Tipiṭaka was made by Robert Childers in his A Dictionary of the Pali Language of 1876. Childers gave about 165 plant names and provided the Linnaean nomenclature for most of these. However, more than half these names are from Pali works composed in Sri Lanka and are not mentioned in the Tipiṭaka itself. Rhys Davids and Stede’s Pali English Dictionary published between 1921–25, includes about 420 Pali plant names with the botanical names for about a third of these. Included also are about 185 animal names of which only eight include the zoological names. It is unclear what authority Rhys Davids and Stede used for the nomenclature they did give but they seem to have relied heavily on Monier-William’s Sanskrit English Dictionary. A thorough compilation of material on flora, fauna and the environment from the Pali Tipiṭaka is more than justified. Despite being a rich source of information on these subjects Indian scholars have largely ignored Pali literature.

Mt. Kailash, A Pilgrim’s Companion

After Mount Everest, Mount Kailash is the most celebrated mountain in the Himalayas. The name Kailash is derived from the Sanskrit kailāśā meaning ‘crystal’. It is 6,714 meters (22,028 ft.) above sea level and some 2000 meters above the surrounding plain. Technically Mt. Kailash is not in the Himalayas but in what is called either the Gangdise Range or the Kailash Range which runs parallel to the Himalayas. Despite its fame it is by no means the highest mountain in the Himalayas, not even the highest in the region.

Mount Potala

After the Buddha himself, the most revered and universally popular figure in Buddhism is Avalokitesvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. Since his appearance in about the first century BCE this beloved bodhisattva has been worshipped with almost unparalleled fervor by the followers of all schools of Buddhism. Though accessible through prayer and supplication to anyone anywhere, Avalokitesvara was believed to abide on a mountain in a remote part of India where, from its lofty and cloud-decked heights, he could be as his name suggests, “the regarder of the cries of the world”. This mountain was called Potala or sometimes Potalaka. It seems that from about the first century CE pilgrims began visiting Potala although records are very scant.