CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

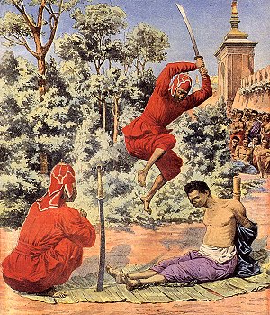

Capital punishment (brahmadaõóa or vadha) is the infliction of death as a judicial punishment. In ancient Indian law there were two forms of capital punishment; quick (÷uddhavadha) which usually meant beheading, and painful (kle÷adaõóa) which included torture before death. The Tipiñaka describes a number of gruesome ways criminals were executed (M.I,87). It also records for us the words of a judge condemning a thief to death. `Tie his hands behind his back with strong rope, shave his head, parade him through the streets to the sound of a harsh drum, take him out by the south gate and chop his head off!'(D.II,321). Horrible and heart-rending scenes were common at the places of execution. We read of a monk pleading with an executioner to dispatch a criminal quickly so as `to put him out of his misery'(Vin.III,86).

The Buddha objected to capital punishment mainly because it involves cruelty and killing, thus contravening the first Precept. He said that judges who hand down cruel punishments, tormentors and executioners all practise wrong, literally `cruel' livelihood (kuråra kammanta) and create much negative kamma for themselves (S.II,257-60).

Buddhism would also say that it is better to try to reform criminals and turn them into productive members of society rather than execute them. The Jàtakas tell a story about a wise king who instituted many reforms, amongst there was `opening the prisons and breaking the executioner's block' (Ja.IV,176). Another king in the Jàtaka says of a wrongdoer: `I punish people according to justice but also with sympathy'(Ja.III,442). This same point was made by the great Buddhist philosopher Nàgàrjuna in the 1st century CE: `Just as a son is punished out of the desire to make him worthy, so punishment should be inflicted with compassion and not through hatred or greed. Once you have judged angry murderers you should banish them without killing them.'

The earliest evidence of Buddhist influence ending the death penalty is King Asoka's forth pillar edict issued in 243 BCE in which the abolition of the practice is announced. At least during some of the Buddhist period in India capital punishment seems not to have been the norm. The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang who traveled through the subcontinent during the 7th century wrote: `The kings of India believe deeply in the Buddha's teachings and do not use the death penalty in governing the people. Even persons guilty of serious offences are not executed.' The Japanese Emperor Shomu, a devote Buddhist, abolished capital punishment during his reign (724-49) and it was abolished again 810 and not used for most of the next 350 years. Tibet abolished capital punishment in 1913. Today all Buddhist countries have the death penalty, although Sri Lanka has had a moratorium on capital punishment since 1997.